More and more, we’re seeing architects and design teams putting operational carbon reporting at the forefront of designs, and that’s great! But, as Project Manager Christina Michayluk explains, you’re leaving a lot on the table if you’re not considering embodied carbon at the design stage too.

The Footprint team sees, first-hand, that conversations around reducing operational carbon are happening on projects across Canada – more than ever, which is great to see. But when it comes to embodied carbon, currently only Toronto and Vancouver have mandatory embodied carbon reporting for new construction. Because it’s not required per code or bylaw in many parts of the country, or there are implications to budgets and project schedules, often embodied carbon conversations don’t move forward (or only occur later in the project phase, which may be too late for any significant impact). By considering embodied carbon above and beyond existing requirements, architects and design teams have the opportunity to position themselves ahead of accelerating energy efficiency standards – and capitalizing on carbon reductions.

The Cost of Carbon Emissions

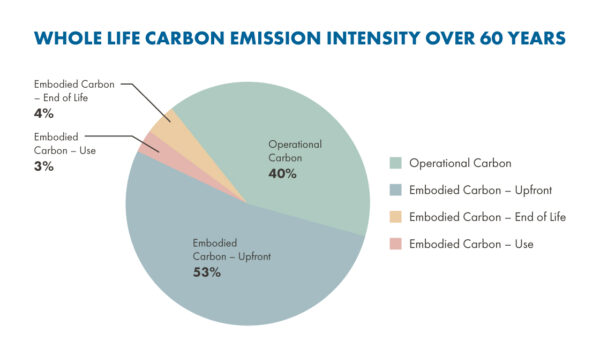

From my perspective, neglecting to look at reducing embodied carbon – that is, carbon emissions from the manufacturing of materials, construction, and end of building life – means missing out on early opportunities to “spend” carbon emissions wisely. Footprint recently worked on a commercial building in Ontario. This project had a rigorous requirement for energy use, however embodied carbon reporting was only added to the scope at the end of design. Our team estimated that embodied carbon (consisting of EC – Upfront, EC – Use, and EC – End of Life) contributed up to 60 per cent of the total emission over 60 years (represented in Figure 1 below), illustrating the scale of the missed opportunity for emissions reductions. If this example included grid decarbonization, operational carbon would also be lower!

As more projects target energy-efficient design, emissions resulting from operational carbon are decreasing. But embodied carbon is “spent” before a building is used. Once a building is completed, embodied carbon emissions can’t be recovered or reduced – in other words, no refunds, no exchanges! In fact, any work completed on the building in the future will just add to the overall emissions.

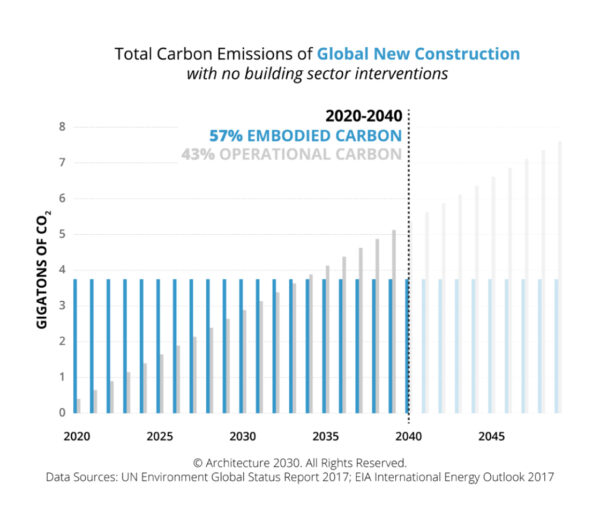

Architecture 2030 reports that, by 2040, without governed reductions of embodied carbon, embodied carbon would surpass operational carbon over the life of a building (figure 2). Early consideration of embodied carbon in a project’s design is essential if we want to achieve Canada’s net zero goals. We must reduce the impact of *all* sources of carbon emissions as much as we can, and embodied carbon is an essential part of this total.

Start Early with Embodied Carbon

So, where should architects and design teams “spend” on carbon emissions on new buildings? This is a huge discussion in the design and construction industry across Canada.

The largest contributors to embodied carbon are in a building’s structure and envelope, which can include:

- Concrete (e.g., slab on grade, piles, footings, foundation walls, footings, etc.)

- Steel (e.g., columns, beams, girts, steel studs, etc.)

- Aluminum (e.g., curtain walls and window walls)

- Reinforcement (e.g., bar and mesh)

- Insulation (e.g., semi-rigid, rigid, batt, spray, etc.)

As you can see, structural materials are key contributors, so exploring structural design options is a lot easier for architects and design teams to do at the early stages. Don’t be scared – there are three great ways to approach this!

1. Have a dedicated scope for embodied carbon analysis.

While there is no standard to regulate embodied carbon emissions in Canada (yet), owners can start adding embodied carbon reporting to project requirements and RFPs. Using the ZCB-Design standard as a framework is a great start.

2. Explore “micro” analysis early on.

The architect and design team can engage life cycle assessment specialists to conduct assessments for envelope studies to compare different façade and assembly options. Pro tip: Be sure to maintain your effective R-values…otherwise your friendly neighbourhood energy modeller might have something to say! The team can also compare specific products and try different insulation and interior finishes (including flooring types and even gypsum), carry out hot spot analysis early on to look at frame types, and explore different concrete mixtures.

3. Aim High(er Than You Think You Should).

If projects are registering for green building rating systems like LEED or Green Globes, we encourage architects and design teams to opt to target the credits that focus on embodied carbon reduction (which also includes additional environmental impact categories). Alternatively, set your “sites” on standards like Zero Carbon Building – Design, which have a threshold for embodied carbon (or a reduction of 10 per cent), as well as innovation credits for further reduction.

No More Missed Opportunities

To meet Canada’s net zero goals, we know we must reduce the impact of *all* sources of carbon emissions. Embodied carbon in buildings represents a significant percentage of global emissions, yet is often overlooked (or left “too late”) in the design process. Unlike operational carbon emissions, which can be reduced over time through upgrades and retrofits, embodied carbon emissions cannot change once a building is completed. To make a real impact on carbon emissions, I would love to see embodied carbon reporting on new construction becoming a part of the conversation between owners, architects, and the design team early on.

Christina Michayluk has dedicated her career to championing sustainable initiatives in the building industry, managing sustainability strategies for a diverse range of clients in Alberta, BC, and Ontario. She is especially passionate about lifecycle assessments, and leverages her extensive knowledge in this area to help clients identify and reduce the impact of embodied carbon on both new and existing buildings.

Sources

[1] “WHY THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT?” Architecture2030, accessed September 12, 2023, https://architecture2030.org/why-the-built-environment/